A money system designed for exponential growth cannot be sustained and produces predictable undesirable outcomes. Understanding the unbending mathematical reality of a pyramid scheme helps explain why this is true. A pyramid scheme is any financial scheme that requires an exponentially growing number of participants and pays early-in participants with newcomers’ contributions.

Back in the 1920s an Italian con man, Charles Ponzi, developed a scheme. He offered people a 50 percent return on their investment in 45 days, or 100% in 90 days. He didn’t invest the money; he simply paid returns out of money coming from new investors – while spending lavishly on himself. If everyone waited the 90 days, this meant as one person’s payout came due, he needed two new investors to pay them out. This was unsustainable. There weren’t enough investors on the planet to keep it going for long, and lots of people lost their money. Charles Ponzi gave his name to a particular kind of financial pyramid scheme. In 2008, a group of investors lost over $ billion to a Ponzi scheme run for over 40 years by Wall Street darling Bernie Madoff, proving people are reluctant to learn from math and from history – and he was a master con man.

Most people understand a pyramid scheme is bad, but people continue to fall for these schemes. Why? It’s worth taking a little closer look, because understanding the math and the motivations of a pyramid scheme helps us understand our current money system and why it remains in place.

In any exponential scheme, the math is an unbending reality: those who jump in early benefit at the expense of those who follow, and only a very small number benefit at the expense of the many. In terms of our money system, this means those who have the privilege of creating new money benefit at the expense of everyone else. (More on that later.)

Pyramids and ‘Circles of Giving’

When I was living in Hawaii I lost a friendship because of a pyramid scheme. Someone had come to the Island with a scheme carefully designed to suck in women. It was called a Giving Circle. An invitational you-are-special-when-you-belong circle of women was meeting every week to discuss their dreams, how to overcome their unconscious blocks to accepting wealth into their lives, how to give this wonderful experience to others, and to empower one another.

The scheme had a well-written back story: The Circle had been started by the wives of some professional athletes in Seattle, who, blessed with wealth and the ability to help other women, wanted to share their good fortune.

The Circle had four courses like a good meal – yum! Love those food metaphors. The idea was that a $5,000 gift brought you into this loving circle of women friends around the table at the appetizer course. You gave your $5,000 to someone who had arrived at dessert. When you brought two more people in under you who gave $5,000, you moved to the salad course. When each of those two people brought in two more, you moved to the main course. And when each of those two brought in two more, you moved up to the sweet dessert spot and had eight people coming in at appetizer giving you $5, each, for a $40,000 total.

It was an illegal pyramid scheme pure and simple. But the participants were told stories about women who used part of their $40K windfall to help another woman get into the Circle, and many were convinced this could make the geometric progression into a circle. The Circle attracted people who hoped to get a high reward for a low investment. And lest you think the women were the only dupes, there was a parallel scheme with another theme going on at the same time for the men.

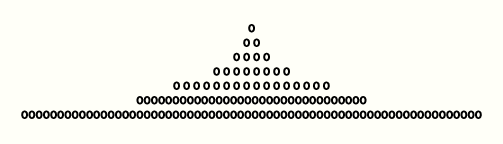

In the scheme outlined above, the mathematical reality is that for one person to get $40,000, eight people must pay in $5,000 each. Since you pay $5,000 to get in the game, you net $35,000 if you’re one of the lucky ones. It only takes 15 total participants for the first person to walk with their dessert. But for the eight people who each pay them $5,000, 64 people will need to be brought in with $5,000 each. For these 64 people to get the payout, 512 people must pay in. Remember what an exponential curve looks like: it looks totally doable in the early stages. However in roughly 30 levels, you would need more people than we have on the planet to pay off any of the last rounds.

That’s it. That is the math. For every person who walks away with the payout, seven people must forfeit their money. Those who are in early may be able to get some or all of their money back, and may even be winners too. But in the total scheme, only one in eight people can be a winner. That’s the simple mathematical reality.

My guess is these schemes get started by thoroughly unscrupulous people. The con artists set themselves up with fake bank accounts to fill the top three layers of a pyramid, giving each identity a creative backstory…a widowed single mom struggling to pay her college tuition, so she can better the lives of her children…a veteran just starting up a business. Helping others is good, and we all want to be helpful, right? These stories make participants feel good about joining in, even if there are little red flags waving in the back of their minds.

The con artists pick a community and spend time at the social centers (coffee shops, churches, etc.) to pick out the vulnerable social leaders. They find social networkers who are hungry for quick money. They fill the first group of eight participants by taking a little time to get to know them and then let them in on this incredible opportunity to give and to receive. This first round of eight will pay $5,000 to the dessert top position, which is one of the con artists using an alternate ID. Now they’ve got eight social networkers with an interest in talking 16 more people into participating, and then 32 more people.

The con artists have taken the seven positions in the top three levels. Each position will earn them $40,000 if they can keep the scam going until all these positions reach dessert and get paid out. The con artists are not contributing anything to anyone, so all their income is profit. Up through this point, if the pyramid developed evenly (every entry at each level finds its two new participants), all the money coming in would go to the creators of the scam in their various IDs. If any of the people below them manage to fill the positions under them – two people, who get two more people, who get two more people – and get a payout it serves to fire up everyone else: “Hey, this works!” The successful early-in players will prove it all works, and will stand as beacons to draw the rest of the moths into the flame.

Once the con artists collect from the top positions, they fade into the sunset with $280,000, leaving the community to the inevitable collapse of the pyramid and the ensuing ill will.

I did my best to point out to a friend that according to the laws of math, out of every eight people who play the game, only one can walk away successful – at the expense of seven other people. It is simply not a circle. Even if every single person who succeeded jumped back in the game with $5K of their $40K take, it would just stretch out the number of levels until the collapse. She accused me of being close-minded, stuck in a poverty consciousness, an obstructionist, and stopped speaking to me. Sigh.

I heard one lovely-spirited woman got in very early and made it to the $40,000 payout. I moved away before the scheme had run its course, and I’ve wondered since how many of the people who paid her got anything back, and how that affected community spirit and her place in the community. Maybe not at all, as people are often willing to say, “It was my fault; I didn’t work hard enough to bring in more people under me.” Or, in hindsight, they say, “Wow! I was sure a sucker, so it’s my own fault.”

With a Ponzi scheme, we see our own effort and not the system that drives the outcome. We also see those who succeed or fail and credit their effort, rather than the system.

It is just so with a money system.

Some win, most lose

In any pyramid scheme there are three types of players: the con artists, the successful participants, and the vast majority who lose their shirts. That should sound familiar to anyone studying our current economic conditions.

However, human existence isn’t a neat and simple math problem. Let’s say my friend who succeeded with an extra $35,000 in her pocket used her new money to start up a business providing a wonderful widget that bettered the lives of many. Say her business became a great market success, requiring more employees and increasing the tax base in her community. Over time, the $35, she took from others created millions of dollars in benefits to the community. Would that make it right?

How could we decide whether the $5,000 loss to the people who funded her windfall and investment was worth the price? It would have an entirely different flavor, wouldn’t it, if the seven people contributed their $5,000 as investors themselves? They would be apprised of the risk and would share in the profits of her enterprise should it succeed. The con gives her success a bad taste; it makes any success that follows rotten at the core, and creates a culture where if it makes money, it’s OK. Does that sound familiar?

Clearly, the losers will see the answer to the worth it question differently, too. Perhaps the loss of $5,000 meant a mom went without the medical care she needed and died, leaving her motherless children dependent on the State – at a cost of millions to the community.

Financial pyramids

Finance is an aspect of our living economy. It is subject to the limitations of any living system, including a finite pool of participants and resources. This means any financial scheme or money system that requires exponentially expanding the supply of participants, money, profits or resources is ultimately doomed to collapse. That is the math and the real world. Keep this crucial understanding in mind as we look at money systems.

Next we’ll talk about why we are so vulnerable to the call of a con.